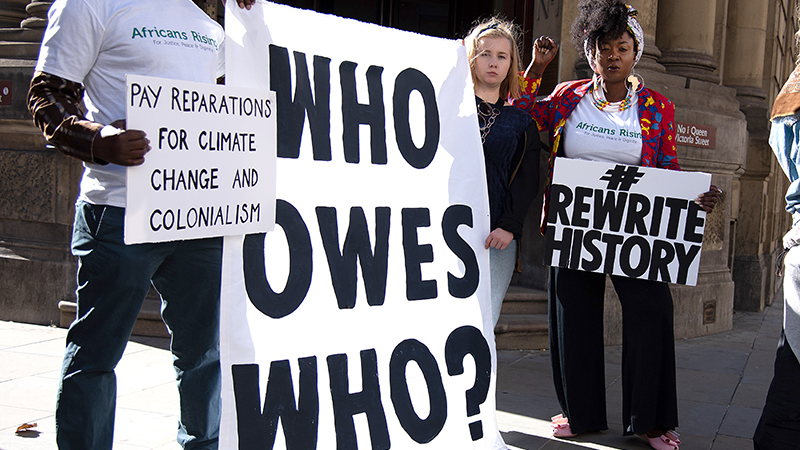

The topic of reparations for the Black community often centers on state-led initiatives or large-scale federal programs. However, the reality is that progress in such initiatives has been slow, inconsistent, and at times nonexistent. For generations, Black individuals and communities have faced systemic racism, economic disadvantage, and a lack of formal redress for historical injustices. The concept of self-administered reparations, which highlights the agency of individuals and communities in addressing their own suffering and building pathways for progress, has emerged as a powerful alternative to fill the gaps left by governmental inaction.

What Are Self-Administered Reparations?

Self-administered reparations represent the strategies individuals and communities use to repair harm and create opportunities for growth without relying on governmental or institutional support. This concept extends beyond simply surviving systemic oppression—it’s about reclaiming autonomy, rewriting the narrative of victimhood, and fostering resilience.

For instance, in post-conflict societies, individuals and civil society organizations often turn to informal methods of repair when formal reparations programs fall short. Whether it’s creating financial cooperatives, supporting local education initiatives, or using cultural memory to maintain identity and dignity, these efforts are driven by a proactive approach to healing. Likewise, in the Black community, self-repair strategies have long been part of the collective response to systemic inequities. The rebuilding of Tulsa’s Black Wall Street spirit after the 1921 massacre and modern movements like group-owned wealth initiatives are prime examples.

Understanding the Historical Context

The fight for reparations has always been closely tied to the deep wounds inflicted during slavery and its aftermath. The systemic denial of opportunities after emancipation—exemplified by the unfulfilled promise of “40 acres and a mule”—cemented intergenerational economic inequality. Programs like the 1862 Homestead Act provided millions of acres of free land to white settlers while excluding freed Black Americans, deepening the disparities.

Racial discrimination didn’t end after slavery. Instead, it evolved into Jim Crow laws, segregation, and discriminatory lending practices, effectively blocking Black families from building generational wealth. Even symbolic reparative steps, such as naming streets after Martin Luther King Jr., often fall short in practice. For example, disparities between predominantly Black neighborhoods and affluent white ones, as seen in Tulsa, Oklahoma, underscore the long-standing effects of these injustices.

Cleo Harris, a descendant of Tulsa’s prosperous Greenwood community—more commonly known as Black Wall Street—encapsulates the importance of self-repair. His store, Black Wall Street Tees & Souvenirs, represents not just economic opportunity but a commitment to remembering and preserving history. Harris’s efforts to educate others on Black history, largely self-taught, reflect the enduring necessity for bottom-up initiatives to keep stories alive and foster progress.

The Importance of Self-Administered Reparations Today

- Empowering Communities

Self-administered reparations allow Black communities to reclaim autonomy by addressing needs on their own terms. Instead of waiting for legislative change or institutional acknowledgment, individuals take ownership of their economic and cultural futures. Financial initiatives, such as cooperative investment groups or Black-owned businesses, help counteract systemic financial exclusion and strengthen community ties.

- Cultural Preservation and Resilience

Repairing the present involves remembering the past. Grassroots organizations, museums, memorials, and educational programs help retain cultural memory and give voice to stories often excluded from mainstream narratives. This approach not only honors those who came before but also strengthens a collective identity that fuels resilience in the face of adversity.

- Filling Gaps Left by Formal Reparations

The harsh truth is that most governmental reparations programs—from Columbia to Guatemala and beyond—fail to provide adequate redress. Likewise, in the United States, H.R. 40, a bill proposing a reparations commission, has stalled for decades despite widespread support. Self-repair efforts serve as stopgaps, ensuring communities have access to tools that promote healing and justice where the state has failed.

Challenges of Self-Repair in the Black Community

While self-administered reparations showcase the strength and resilience of the Black community, they also highlight the injustices of systemic neglect. By leaving people to their own devices, governments risk perpetuating the very inequities reparations are meant to address. There remains a critical need to shift societal values, hold institutions accountable, and amplify the effectiveness of formal reparation programs.

At the same time, narratives of victimhood must be reshaped to include more comprehensive depictions of agency, empowerment, and resilience. Scholars such as Dr. Ron Daniels and William Darity point out that even centuries-old debts must be acknowledged for true justice to begin.

Building a Balanced Future

Self-administered reparations should not replace government responsibility but complement it. By integrating formal and informal measures, we can create a more effective and inclusive approach to addressing historical wrongs. When governments and communities collaborate, reparative justice becomes not just about restitution but also about building equitable futures.

To the Black community, self-administered reparations function as acts of defiance, hope, and progress. From community-run initiatives to entrepreneurial endeavors, these actions not only aid survival but spark cultural and economic renewal. They remind us all that while waiting for systemic change, we can take ownership of our futures today—and ensure the next generation’s success tomorrow.

Article reposted from STL Argus News read in its entirety here.